Language is an intricate art. Created over centuries, it is always in motion, alive, carrying a multitude of different workloads, meanings, and emotions.

I would like to discuss my native language, Russian, and the challenges of translating some unique characteristics of the language, which can lead to a loss of expressiveness and emotionalism in the translated texts, especially in poetry and fiction.

Let’s begin with the Russian names. The creation of many nuances in Russian names, especially first names, and the meaning of last names, which can often be difficult for translators to convey in foreign languages, could be a great help in understanding literary characters for Russians immediately, but not for foreign readers.

Dostoevsky. Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov- the root of this name is “raskol”. Every Russian, opening this novel, already understands the main character of the novel because of the meanings of “raskol”— dissent, split, division. All these are the characteristics of Raskolnikov. Minor character, alcoholic Marmeladov, as sweet as “marmelad” - in Russian, marmalade- in English, but you can’t trust his marmaladery: he pushed his daughter Sonechka to prostitution to save the family,

Idiot. Lev Myshkin- a combination of the strongest animal, lev -the lion, and the smallest, weakest mysh -mouse. This is Dostoevsky’s representation of himself as Christ.

Brothers Karamazov. Smerdiakov- son of Lizavety Smerdiashchey. Smerdit’- to stink.

These examples came to my mind suddenly, but all Russian writers used so-called “telling” names. Playwright Fonvizin of the 18th century was so witty that we repeat after his character Prostakov - “simpleton” that we don’t need to study geography because carriers take you anywhere, even more now, in the 21st century.

The most interesting story in the Russian language happens with our first names.

The first name, given by parents to the newborn child, is his/her formal name, for example, Anna. I love this name because of its musicality. We pronounce it slowly with the stress on the first ”a” and double sonorous “n” sound as the musical notes. Because of its musicality, both poets and writers love this name, just to remind Blok’s Donna Anna, or Esenin’s Anna Snegina, or L. Tolstoy, Anna Karenina; there are four of each of the sonorous “a” and “n” that make the title of the novel so beautifully sound.

But how do we use the name Anna in some Anna’s life? We never call a child by its formal name. With the help of suffixes, we make many derivatives of the first name, and we use them according to the moment.

First, the short neutral name of Anna is Ania, or Ana, where in the first, “n” is pronounced very softly, and in the second,”n” is hard. We can add a suffix -echk, an ending “a”, and get the sweet Anechka. With the help of other suffixes, we got Aniuta, Annachka, and Annushka. We can also use the disdainful suffix “k”, the children use it a lot, and Anechka quickly becomes nasty An’ka (‘soft n'), or Aniutka. So, there is a long line of derivatives of the first name:

Anna- Ania, Aniuta, Anechka, Aniutochka, Annushka, An’ka, Aniutka. And maybe more, it doesn’t come to my mind right now.

There are many more derivatives, for example, of the favorite character of Lev Tolstoy, Natasha Rostova. Her given first name is Natal’ya. She is Natasha only in her childhood, and later, only to relatives and close friends. We can use her short name, also known as Natali, or her affectionate nicknames, such as Nata, Natashen’ka, or Natalochka. When angry, we can use - Natashka.

I don’t think our derivatives are synonyms for American or English nicknames, because they are not substitutes.

At the age of 16, we receive our passports, our primary document of identification, where our full name is written:

Last name - father’s last name - Asanov, as it appeared in my passport - Asanova, where the ending “a” indicates my feminine gender.

In my brother’s passport, our mother’s last name- Trefilova, so in his passport, his name was Trefilov.

First given name- Larisa, mine. My brother’s name was Boris.

Patronymic - father’s first name. My father’s name was Nikolai, and my patronymic became- Nikolaevna, with the help of the suffix: “evn”

So, now my full first name has become Larisa Nikolayevna, which I will be using in official situations only. For instance, after University, I was sent to teach the Russian language and literature in a village school. I entered a class of pupils and introduced myself to them: 'My name is Larisa Nikolaevna.'.

My brother’s father’s name was Timofey (he never knew him), so he became Boris Timofeevich, with the help of a suffix: evich.

My full name is Larisa Nikolayevna Asanova.

My brother’s name- Boris Timofeevich Trefilov.

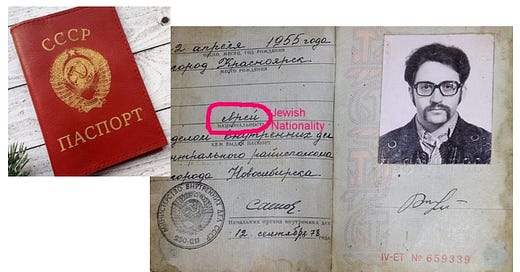

Besides our names, our passport indicates our nationalities. In my passport, I am Russian. In my husband’s passport, he is a Jew. When a Jewish person was not getting a job for which they had applied, they could answer a friend that they didn’t get the job because of paragraph 5. Not necessary to explain anything more.

Place of work.

Marriage, if he or she married.

However, we are now discussing our names and how we can convey the nuances of our relationship through them. And in my mind comes Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Mary, in English. Mary is a common name. ( I am not talking about religion), nothing exceptional in it for a Russian ear. However, in Russian, Nabokov titled his novel Mashen’ka, and every Russian, even without having opened and read the novel, understands that Mashen’ka is the first love of the main character because the meaning of the suffix -en’k is endearment, softness, and caressing deminutiveness of love.

This was lost in translation…

PS. Any questions about Russian names or translation from English into Russian are welcome.

Fascinating! I'm enchanted...

That was great Larisa very interesting thank you